Camille Paglia Perfectly Justified Madonna's New Grammys Look - 30 Years Ago

Her early-90s analysis of the global superstar is even more relevant today.

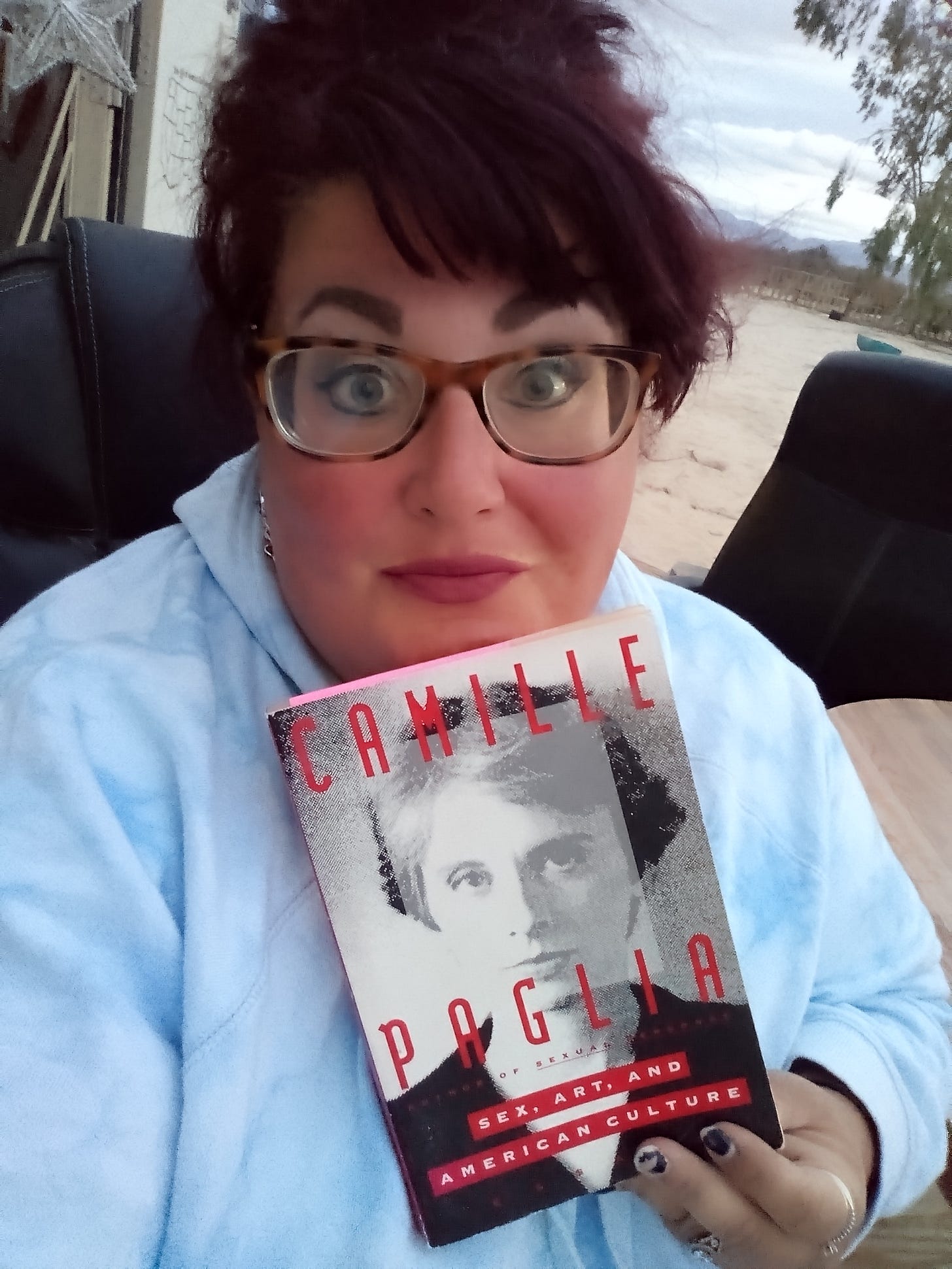

As puffy sleeves and oversized, Glinda the Good Witch skirts took center stage at the 95th Academy Awards on Sunday, I happened to be reading Camille Paglia's fascinating book, Sex, Art, and American Culture, and my attention was brought to another recent awards show - the 65th Annual Grammy Awards, back on February 5. I opened Paglia's essay collection at the beginning, and was immediately met with an essay about Madonna, who made early-February headlines for the bold, seemingly Botoxed look she sported at the Grammy ceremony, where she was on hand to present to Sam Smith and Kim Petras, the first transgender and non-binary duo or group to win a Grammy.

True to form, she showed up in a dominatrix-y getup complete with riding crop. But, fashion choices aside, she looked very different, maybe even unrecognizable. And she took a lot of flak for it, including from leftie millennial ladies like myself, who grew up with Madonna and her radical sexual-maverick persona already established. Because of that, it seemed to me that the clucking over Madonna, of all people, seemingly caving to societal pressure to appear eternally young, missed the mark somewhere. I just couldn't quite put my finger on it.

But last Sunday, Camille Paglia supplied the answer. From all the way back in 1990.

In her New York Times piece, “Animality and Artifice,” she writes primarily in reaction to the shocking, overtly sexual music video for Madonna's song “Justify My Love.” But, from the vantage point of 33 years later, her remarks are perfectly on point in the context of any of Madonna's image or career moves. Paglia frames it this way:

Was this a radical stance in 1990, seven years after Madonna burst onto the scene with her voice, her moves, her lingerie as outerwear, and her refusal to behave “properly?” Maybe! I can't quite tell: I was only five then. But it sure rings true now, decades after Paglia crafted it.

Where did that aggressively nonconformist woman go, though? Through career evolution after image shift after experimental sound over the decades since those early hits, “Holiday” and “Lucky Star,” Madonna has always been an iconoclast. And the fact is, all the little girls who wished our parents would let us go out in ropes of pearls, fishnet gloves, and a tutu are now staring down 40, 45, and 50. And as we reassure ourselves that we're at peace with that lady in the mirror, perhaps it's disquieting to think that the icon who once famously told us, “Beauty’s where you find it / Not just where you bump and grind it," has changed her tune, and is now bowing to societal pressure - or, worse, to men's beauty expectations - never to show signs of growing older.

But that's far too simplistic an analysis. Camille Paglia knew this back in 1990. In the conclusion to her article, she writes:

And she was: Madonna absolutely was the future of feminism at that time. Paglia was correct.

“The eternal values of beauty and pleasure,” however, are not created merely for the onlooker. They're not always - if ever - calibrated to men's ideas of beauty. In fact, they needn't even inform or meet women's ideas of beauty! I realize now that Madonna's versions of beauty and pleasure are the looks and aesthetics that she finds beautiful, pleasurable. It's not for me. It's not for you! It's for her.

Feminism is supposed to be about choice, about freedom. And what we see from Madonna is - has always been - her exercising both, with delightful eccentricity. Undeniably, Madonna is who she is, whomever that may be on a given day, for herself and for her art - not for her fans, and absolutely not for her detractors. That's why she's so different, so revolutionary. And for her pains, now, in 2023, Madonna's whole body having been analyzed to death, her face is being up for dissection and debate! Not only that, but that 64-year-old, endlessly variable visage is now expected to serve as a support structure for the inflamed neuroses of the women she tried to inspire, but who didn't quite put it all together.

Feminism gives us choices. It celebrates all choices - all of the many, many ways to be a woman. There are so many ways to look, to act, to live, to find beauty and pleasure. At its best, feminism removes judgment and celebrates authenticity. And yes, sometimes authenticity is found in artificiality.

That's why it's so beautifully serendipitous to come across two of Paglia's final lines, written in 1991, at this moment in time and culture:

“Feminism says, 'No more masks.’ Madonna says we are nothing but masks.”

Indeed.

Now, come on! Vogue.